Ernst Haeckel

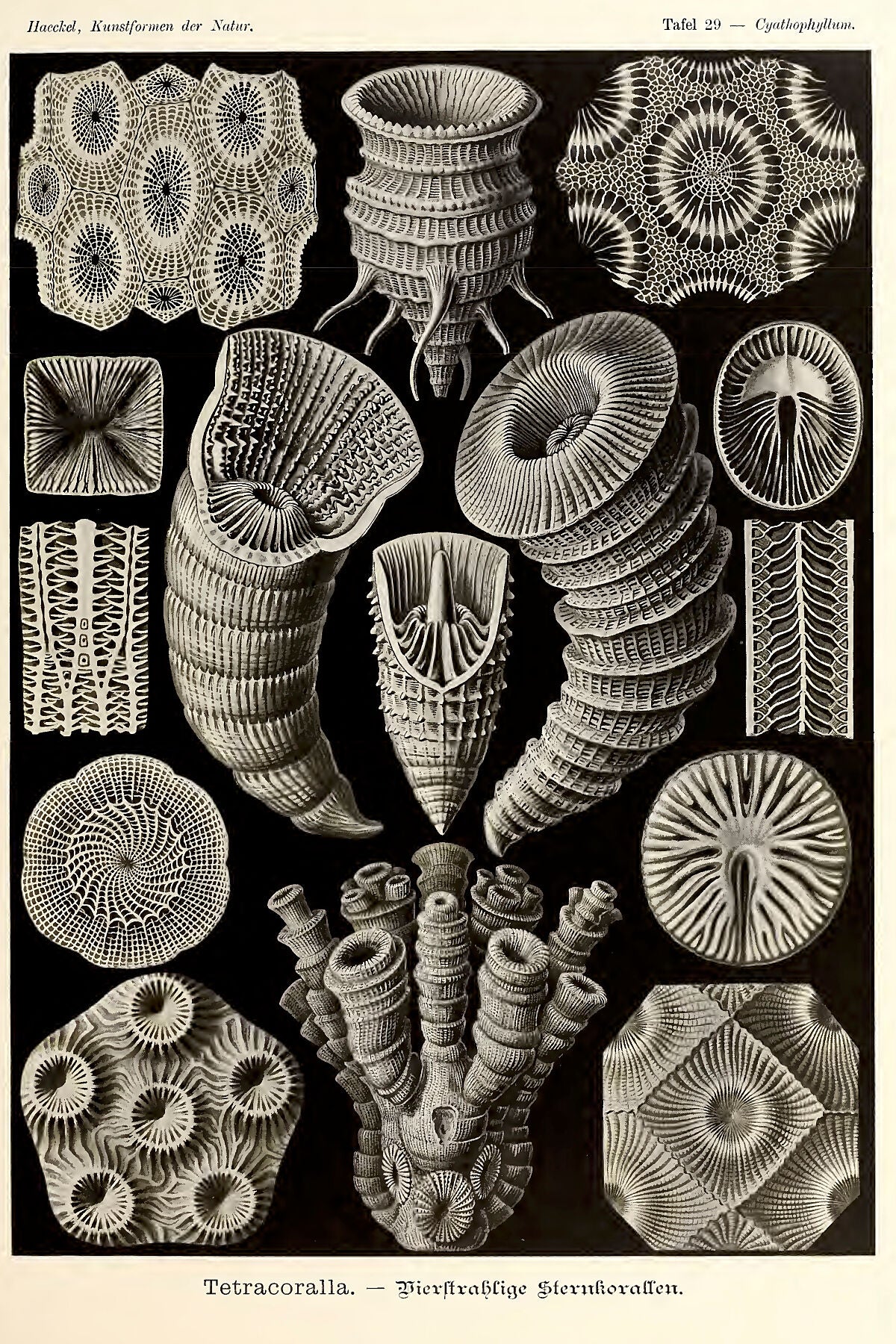

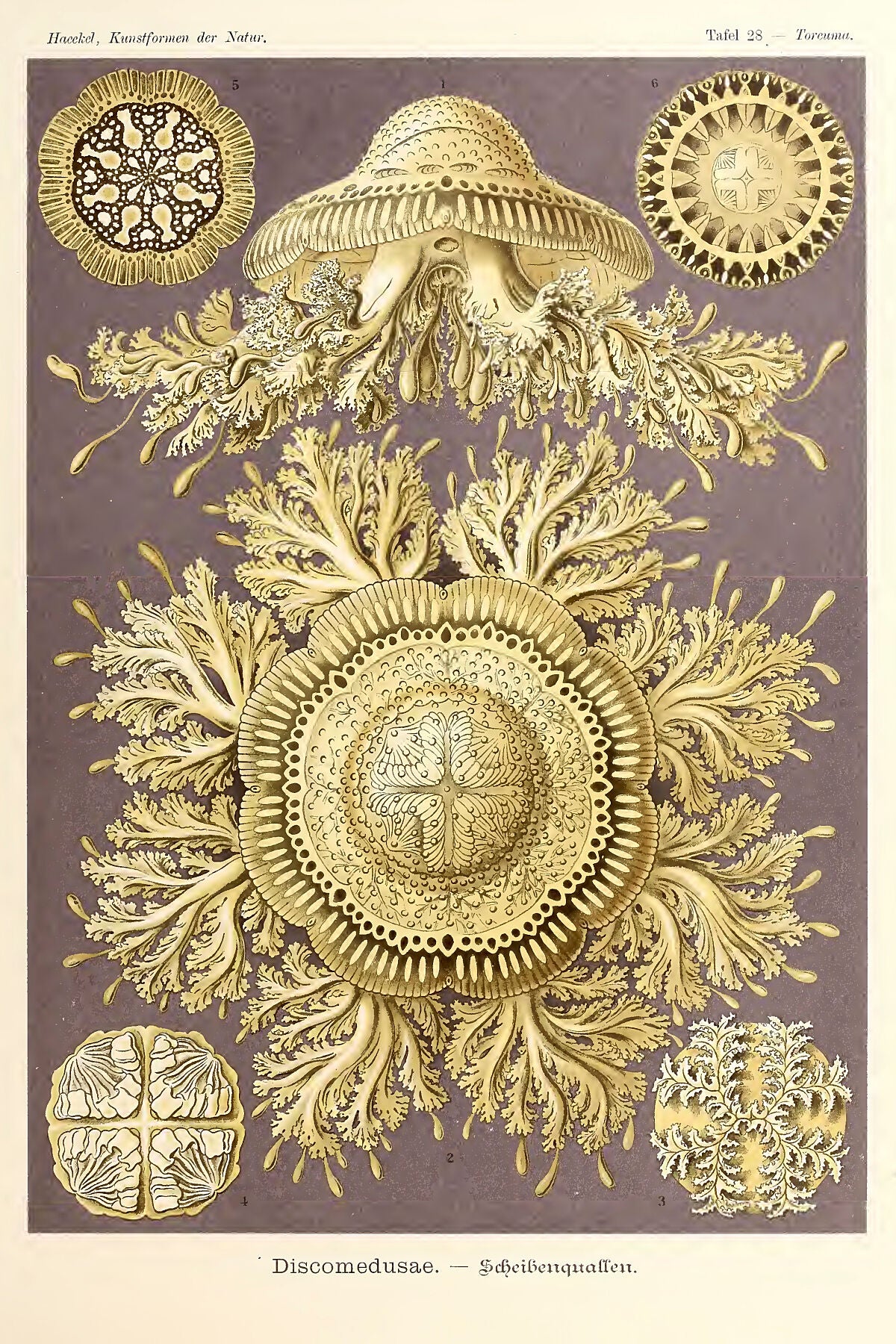

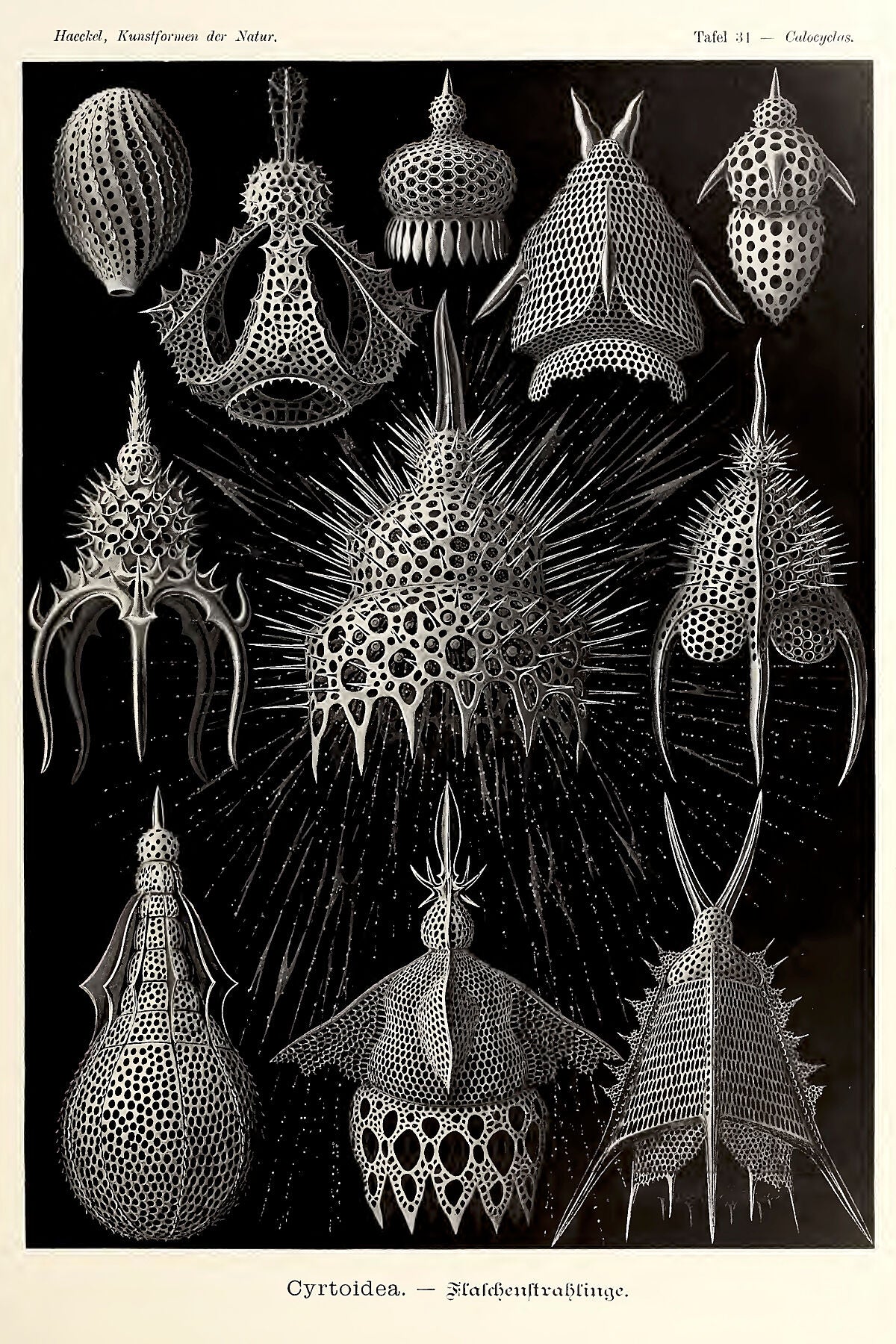

Before macro photography showed us tiny things in great detail, Ernst Heinrich Haeckel (16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) drew life seen through his microscope. The German scientist’s lush drawings, watercolors, and sketches of lifeforms “from the highest mountaintops to the deepest ocean” were published in 59 scientific illustrations between 1860 and 1862. Many of Haeckel’s illustrations feature in his series Kunstformen Der Natur (Artforms in Nature), a “visual encyclopedia” of living things. He was able too see the beauty in the microscopic. For added oomph, Haeckel coined the terms “stem cell” and “ecology”.

Nowadays most of us accept the presentation of life in a classified world shaped by evolution and Natural Selection but in the 1860s Haeckel was attacked by State and Church as a “preacher of immoral doctrine and an arch infidel”. His works were a “fleck of shame on the escutcheon of Germany”, “an attack on the foundations of religion and morality.” Haeckel’s thinking was attracting the kind of publicity money could not buy. Huge success came his way. His philosophy-of-nature book Die Welträtsel (The Riddle of the Universe) became an international bestseller in 1900, selling over half a million copies in Germany alone.

There were other controversies less palatable to our modern tastes and for scientists of an empirical bent demonstrably wrong. For Haeckel, all life including human races operated in a hierarchy, with Teutonic Germans at the pinnacle, natch. (the man wanted to sell books to his contemporaries; best to stroke their egos and his own, even if the science is fatally flawed). Eugenicists and Nazis who met these exalting standards of human improvability through selective breeding and murder lapped up the self-aggrandizing nastiness.

More of his thinking was outlined in an address to the German Monistic League, the group he set up in 1906. Science was right and Divine Providence was bunkum. All answers to the great mysteries of life lay in the physical world:

“First in importance in my opinion is the consistent aim to have science regarded solely and alone as the source of any rational world conception at the exclusion of all so-called revelation, of all ideas and dogmas which attempt to explain the world of phenomena in a supernatural way. Hence all transcendentalism, all belief in the miraculous, is excluded—without detracting from the great value which these products of creative imagination can possess for our emotional life as forms of poetry, and in a wider sense of art. They must not cloud the clear light of knowledge which, pure reason, on the basis of experience and experiment, disseminates over the profuse variety of phenomena.”

– Ernst Haeckel